Peter Morley's tale of his WD Triumph

Old Bike Mart published my account of my introduction to motorcycling in June. Now I’ve found the bike my dad went to war on, or one very like it, thanks to OBM. A military Triumph 3HW was posted for sale in the August edition. I discussed it with the seller who was clearly a genuine enthusiast with an honest bike for sale. We agreed a price and I drove to North Somerset with my trailer to close the deal and collect the bike.

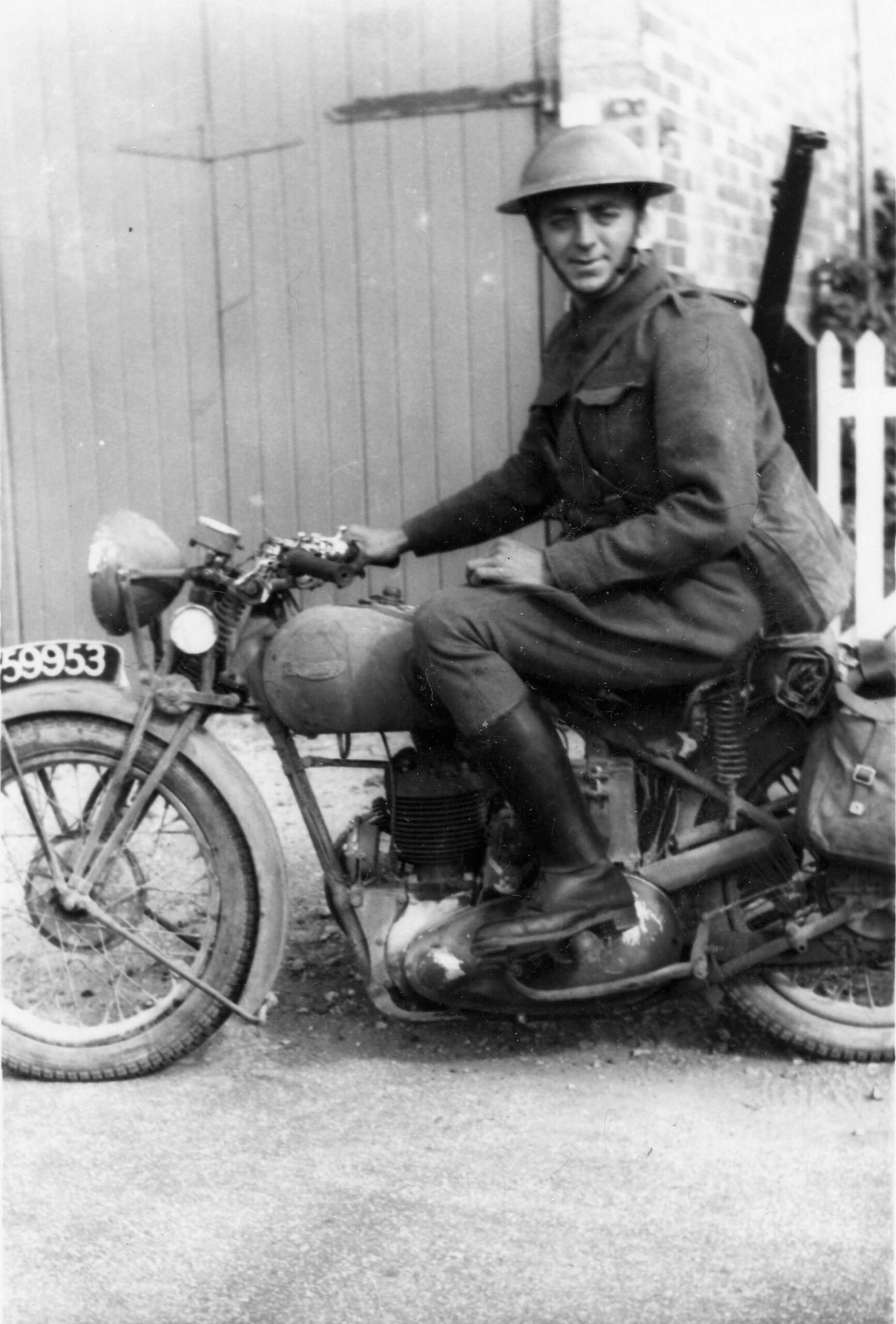

This 3HW was purchased by the WD under Contract Number S5340 in 1944. The bike my dad is pictured on in early 1940 would have been built in Coventry, in the Priory Street factory that was destroyed by bombing in November 1940. Jigs and tools that could be salvaged were set up in a temporary factory in Brackley Street, Warwick, and a new factory was established in Meridian in 1942 where my 3HW would have been built.

The machine I have is 3HW (350 cc OHV). Some sources suggest the 3HW was first made in 1940 and most agree it replaced the 3SW for military use in 1942, with production continuing until 1945. My Dad’s bike could have been a 3SW (350 cc SV) or a 3HW it’s difficult to tell from the photos. My Triumph looks pretty much the same.

The WD tried to standardise, with as many common parts as possible between manufacturers. The standard was settled as 350 OHV and 500 SV with the 350’s in lightweight frames favoured for Dispatch Riders. The Triumph 3HW weighs in at 250 lbs. These machines were manageable over rough ground and could be man-handled when necessary but were powerful enough to enable good progress.

My 3HW has matching engine and frame numbers. I understand this is fairly unusual. You can see from old photos of army workshops that maintenance was an almost conveyor belt operation. Machines would come in, get stripped, refurbished and probably fitted with a replacement engine and gearbox, already overhauled and sitting on the shelf. As my bike was put into service in 1944, it may have not seen a lot of military use. The record plate on the bike (originally riveted to the rear mudguard) shows it as one of Contract S5340, a batch of 4000 bikes. The production table indicates this was split with deliveries to Littlewoods in Liverpool – for consignment to the Far East, Army vehicle receiving depots (VRDs) and Mars in Slough. Apparently, the Slough machines were for the RAF, so mine could have been used for running around and between air bases in the UK. The underlying paint seems to be khaki, which would be correct for the RAF – they didn’t change to blue-grey until after the war.

From production tables, reproduced by Orchard and Madden in British Forces Motorcycles, more than half a million British, and a few American, bikes were procured. These were mostly BSA, Norton, Matchless, Royal Enfield, Sunbeam and Triumph. 20548 were left behind ant Dunkirk alone, according to BBC Press Office release.

The DR was the primary means of passing orders and dispatches during engagements. Radio was considered unreliable but with the DR the safety of the message was the most important thing and they were inspired by their motto, “Swift and Sure”. During Operation Dynamo, the evacuation of Dunkirk, orders were passed to the units holding the ‘Strong Points’ that guarded the perimeter. These orders were usually, “Hold your position.” If you visit the Commonwealth War Graves in the area you will see the headstones of men of the rear-guard regiments and one or two of the Royal Signals – the dispatch riders. Dad made it home but left his Triumph near Dunkirk.I love the history of my bike. It is a genuine WD machine, similar to Dad’s but it has its own history too. It was ‘civilianised’. The previous owner said he bought it intending to put it back into khaki but thank goodness he didn’t get around to it. It is a real relic of the post war austerity years of Baby Boomers, prefabs and orange juice and cod liver oil.

This bike was sold as army surplus to a dealer in Bristol who slapped on a bit green and some black paint and sold it in 1948 as a get-to-work transport for men home from the war and re-joining the workforce to pay off the war debt and raise a family.

I understand these 350 Triumphs are quite rare today. Although 30,000 were made, many were lost during the war and, when the opportunity for a bit of leisure came along in the early fifties, the engine was found to be good for grasstrack or trials competition resulting in survivors being adapted for this purpose.

So, my 3HW will keep its colours and help me to remember how far we have come – from the day my dad went to France with the BEF, during the austere years of my childhood and through a lasting peace – to a time when an old man, who never needed to go to war, can indulge in a bit of nostalgia and a lot of gratitude for the men and women who made it possible.